|

|

Our independent, investigative journalism about the U.S. food system is supported by members and donors like you.

|

|

Become a Member for $6/mo.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tomorrow, our members will receive yet another outstanding issue of our members-only newsletter, The Deep Dish. From seasonal book guides to in-depth reporting on climate change, food security, urban farming, Indigenous Foodways, and more, the Civil Eats team has produced 32 issues of this exceptional monthly mini-magazine. And we know our members appreciate The Deep Dish because this year alone it has garnered an exceptionally high open rate of 82 percent, which is about 40 percent above the industry average.

While providing unrivaled reporting for our members is our top priority, we’re also honored that The Deep Dish has been critically acclaimed. Our newsletter has earned a 2024 Excellence in Newsletters award from the Online News Association as well as the digital media award from the International Association of Culinary Professionals for best newsletter.

|

|

The Deep Dish is just one benefit of becoming a Civil Eats member. From November 1 through December 31, your donation of up to $1,000 will be doubled by NewsMatch partners.

Donations of $60 or more provide you with access to Civil Eats annual membership benefits, which include our members-only Slack channel, and our live, community-building salons. If you’ve been thinking about becoming a member of Civil Eats, this is the best time to do it. Donations of $100 or more also will include a sustainably sourced, limited-edition Civil Eats tote bag.

If you’re already a member, thank you! You can still participate in our NewsMatch campaign by making a donation. Every dollar of your support will be matched. If you believe in the work we’re doing, please consider giving today to double the impact of your donation. If you feel inclined, please share this newsletter with someone you know who will appreciate Civil Eats.

Thank you for believing in journalism that makes a difference.

|

|

Support Our Work

|

~ The Civil Eats Editors

|

|

|

|

Restoring a Cornerstone of the Local Grain Economy

|

BY DANIEL WALTON • November 20, 2024

|

Two hefty, seven-foot-tall machines stand in a corner of the airy, white-walled Carolina Ground warehouse in Hendersonville, North Carolina. One framed in light pine wood, the other in gleaming stainless steel, they project an aura of massive force—especially once they start to move.

These gristmills use a pair of huge cylindrical stones, each about 4 feet wide, 2 feet thick, and weighing close a ton apiece, to pulverize wheat and other grains. With a dull roar, like the sound of heavy rain and hail on a metal roof, they gradually crush the kernels between them into a cascade of flavorful flour. Brown paper sacks filled with the soft flour are stacked on pallets near the facility’s loading dock, ready for distribution.

“Every town in the U.S. probably has a road that has ‘mill’ in it,” says Michelle Ajamian, who owns a small mill in Athens, Ohio (and in fact happens to live on a Mill Creek Road). But the era of the neighborhood mill disappeared long ago. Now, although local mills have been gaining traction as part of the whole-grain movement, they are still rare. Just three companies—Ardent Mills, ADM Milling Co., and Grain Craft—own 57 percent of the country’s wheat processing capacity. Of

the more than 21.5 million tons of wheat flour milled domestically in 2022, over 96 percent came from the 21 largest millers and entered the commodity market that fills supermarket shelves across the country.

The Craft Millers Guild is working to change that. Ajamian established the guild in 2020 to provide a voice for a new generation of millers who draw inspiration from historic practices and are trying to restore regional grain economies that have been lost to industrialization. Read the full story.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Op-ed: Food Security Is Urgently Needed in Black Rural Appalachia

|

BY MYA PRICE • November 19, 2024

|

Growing up in Lexington, Kentucky, I spent countless hours listening to my grandmother’s stories. She often spoke of her life in Monticello, a small town in Wayne County, deep in Appalachia. Despite the beauty of the surrounding farmland, food was often scarce. With few grocery stores, long distances between places, and unreliable transportation, my grandmother frequently relied on canned and packaged foods. Fresh produce was a rare luxury, and when it was available, it was often too expensive. The anxiety of not knowing where her next meal might come from haunted her, and her stories of hunger left a lasting impact on me.

Appalachia, a mountainous region

spanning 13 states in the eastern United States, stretches from southern New York to northern Mississippi and is often associated with rural poverty, rugged landscapes, and rich cultural traditions. In Kentucky, it encompasses the state’s easternmost counties, including Wayne, one of the most economically distressed areas in the nation, where residents struggle with limited access to healthcare, education, and food.

Despite a slow decline in food insecurity from 2010 to 2020, the rate in Appalachia is still 13 percent, which remains above the national average of 11.5 percent. In the central part of the region, the issue is especially persistent, with 17.5 percent of residents sometimes lacking access to enough food for an active, healthy lifestyle. With nearly 23 percent of Black individuals in the U.S. experiencing food insecurity, a rate almost 2.5 times higher than that of white individuals, the lack of food access especially impacts Black residents of

Appalachia. Read the full story.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fighting the Corporate CAFO ‘Takeover’ of Rural America

|

BY TILDE HERRERA • November 18, 2024

|

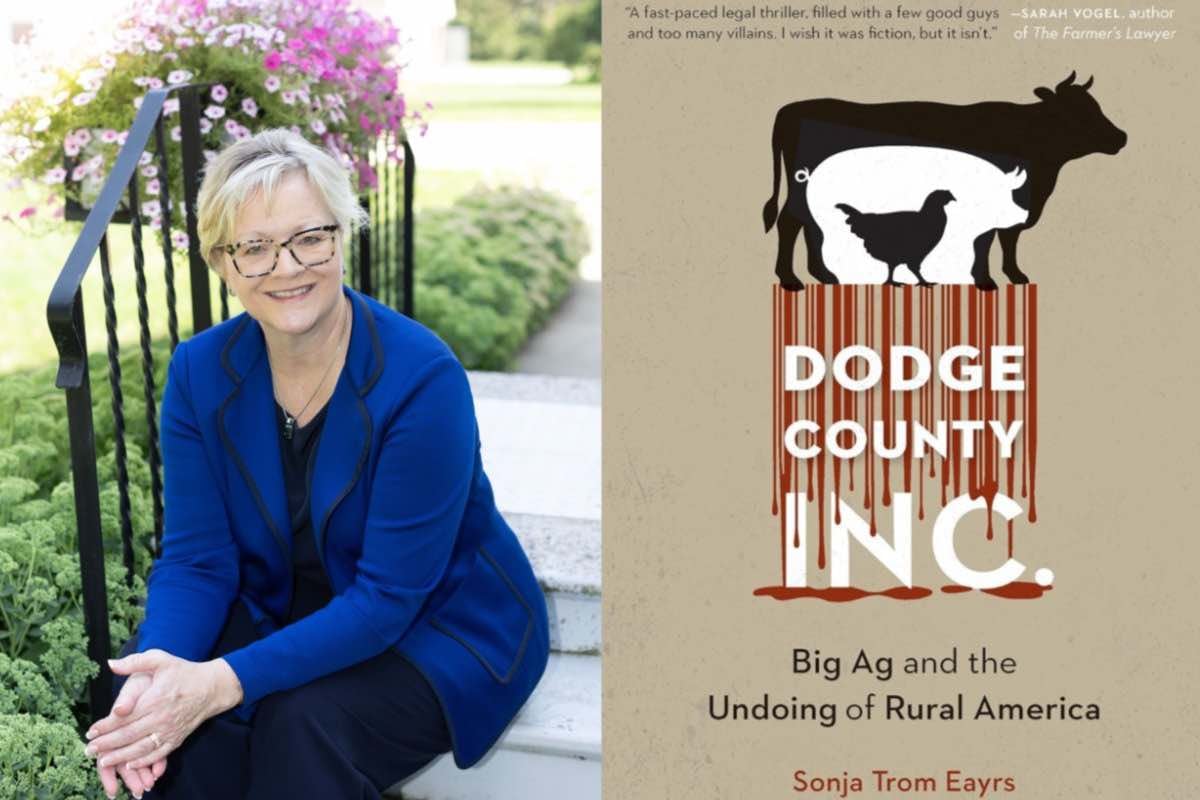

In 2014, Lowell and Evelyn Trom learned that a farmer wanted to build a concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) across the road from their family farm in Blooming Prairie, Minnesota. By then, there were already 10 CAFOs within a 3-mile radius of their 760-acre farm, so they knew the stench the facility would bring.

The proposed CAFO would hold 2,400 pigs and produce as much manure equivalent as a town of nearly 7,000 people. “Enough,” Lowell said, “is enough.” The couple sued, assisted by their daughter, Sonja Trom Eayrs, a Minneapolis family law attorney who felt a deep sense of responsibility to help her elderly parents. Their legal battle took

three years, and by the time they lost, nothing had changed—except a county ordinance had been created that made it easier to greenlight even more CAFOs. The CAFO they fought was built and is still operating across the road from their farm today.

The battle inspired Trom Eayrs to become a rural activist and help other communities fight what she calls a CAFO “takeover” of the Midwest. And it prompted her to write a book about her late parents’ experiences: Dodge County, Incorporated: Big Ag and the Undoing of Rural America, published on November 1. Read the full story.

|

|

|

|

|